Live Tides

NOTICES TO MARINERS

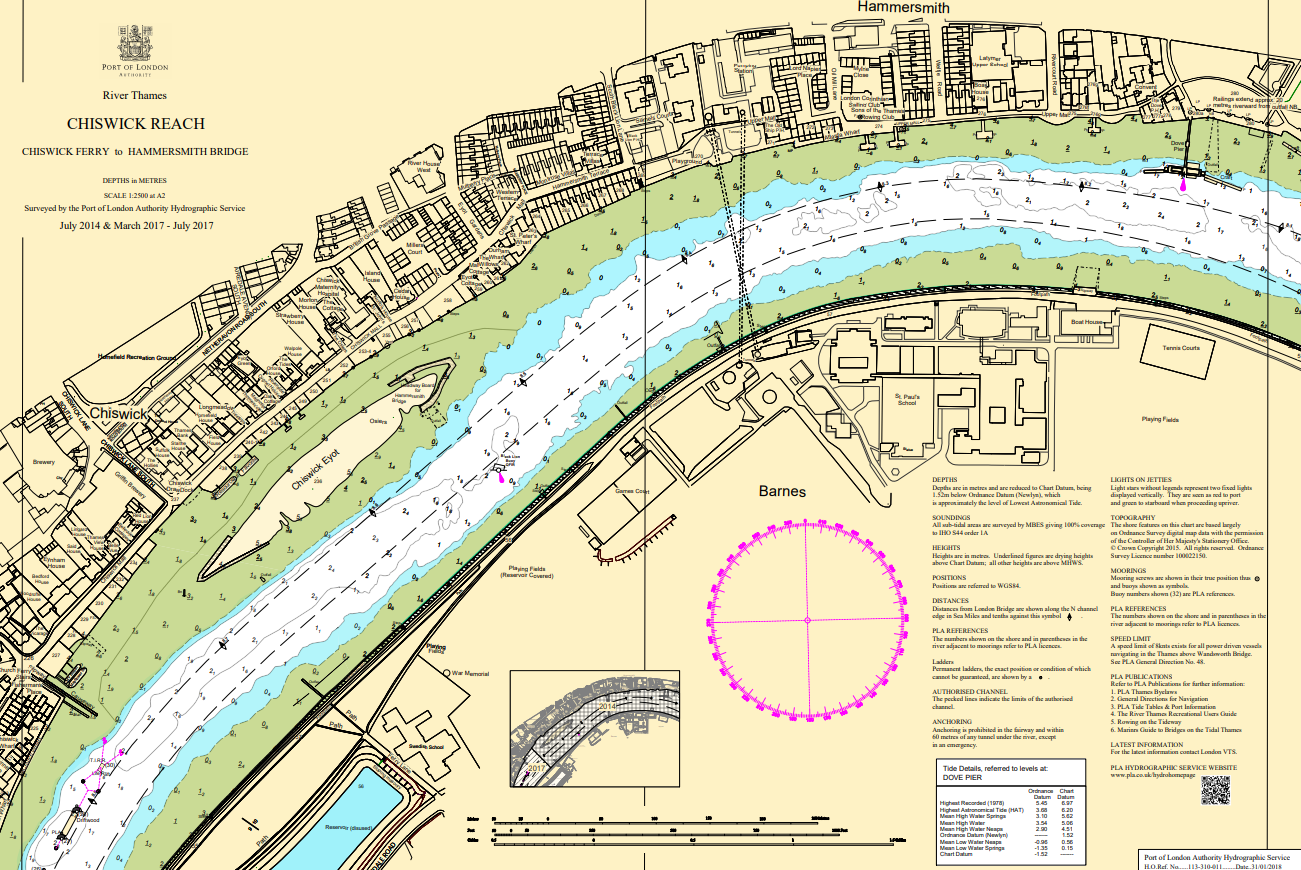

Charts & Surveys

Incident reporting

Life-threatening emergencies on the river:

Call 999 and ask for the Coastguard

For near miss, safety observations and incident reporting click below

Mudlarking bestseller

Lara Maiklem

The publication of a second book about mudlarking on the Thames, an exhibition at Southwark Cathedral and TideFest (12 September) mean a busy end to summer for Lara Maiklem.

Road to the river

“I grew up on a farm in Surrey, only about 30 miles as the crow flies from central London.

“It was a green oasis in a sea of suburbia, bounded on one side by the London to Brighton railway line.

“My first memory of the river is feeding and being chased by geese at Thames Ditton, where my grandparents lived, when I was about three.

“I moved to London in the early 1990’s and discovered the river as a place I could go to escape the chaos of the city.

“For years I walked the river paths and spent hours staring at it until one day, about 20 years ago, I found myself at the top of a set of old wooden river stairs looking down onto the foreshore at low tide and decided to go down and get muddy…. “

Lost and found

“The first time I went onto the foreshore I found a clay pipe stem. It made sense to me that there was probably more to find, so I went back again and again. Every time I found something different.

“The foreshore is a huge historical lucky dip. You never know what the tide will wash up next. That’s what fascinates me.

“The objects I find are mostly just rubbish, the things that ordinary people threw away and lost, but each one is unique and tells a different story about the river and the people that worked on it and lived beside it.

“Bending down to pick something up that hasn’t been touched since the last person lost or dropped it, sometimes over 2,000 years ago, is just magical.

“It’s the best feeling in the world."

Special finds

“I’ve found gold and coins dating back to Roman times, but my passion is for the ordinary, everyday personal objects that were part daily life: pins, thimbles, dress clasps, buttons, children’s toys, the type of things you don’t see in most museums and that tell the most intimate stories of the past.

“Anything with initials, names or dates scratched onto them are particularly special, because they are links to actual individuals from the past.

“I have a 17th Century bodkin, with the initials S.E. scratched onto it; a Roman game counter with the numeral X scratched into the back, possibly to turn it into an illegal gambling chip; and a Victorian penny turned love token with the name J Tweedy and the date 19 April 1864. Who was J Tweedy and why was the date so special…?”

A shoe story

“Probably the most personal object I have is a complete Tudor child’s shoe.

“Thames mud is anaerobic, which means there is no oxygen to degrade the objects cocooned in it.

“When I pulled the shoe out of the mud it was as perfect as the day it fell in, I could even see the soft imprint of its previous owner’s little toes and heel.

“It took me two years to find somewhere to professionally conserve it for me, now it has pride of place in my collection.”

Wildlife haven

"The river is such a wonderful natural artery through the city.

"I once saw one of the peregrine falcons that roosts on top of the Tate Modern swoop down and catch a pigeon mid-air, above the river in front of me.

"There was a lot of squawking, a puff of feathers and it was gone.

"I’ve also seen foxes slink down to drink at the water’s edge at dawn; eels have slithered over my boots, seals have turned their dewy eyes on me and once found a seahorse (sadly dead) on the foreshore in front of the Globe at Bankside."

Reluctant writer?

“Oddly enough, I never really wanted to write a book.

“I’ve spent my entire career working in publishing, but I’ve never been a frustrated author.

“Perhaps I knew too much about the process to want to put myself though it – writing a long memoir-type book is all-consuming and exhausting.

“Mudlarking, my first book, only came about because of my very lovely and persuasive agent.

“She initially contacted me through my Facebook page, which I began in 2012, to ask if I had ever thought of writing one.

“I actually almost deleted her message, but we eventually met up for a chat and before I knew it, I was writing a proposal for a book.

“It was all very fast and quite surreal, not at all like most people’s experience of trying to get published. “

Writing inspiration

“I started writing my first book, Mudlarking, in 2016. I wrote three versions and it eventually published in 2019.

“Writing my second book, A Field Guide to Larking, during Lockdown was much easier and faster, around five months from planning the contents to sending the final files off to the printer.

“My background is in illustrated non-fiction publishing, so I was in my comfort zone and I had the most amazing team to work with, including foreshore archaeologist Mike Webber and the wonderful artist Johnny Mudlark.

“It was a dream project for me.”

Putting pen to paper

“All books start with an initial idea that you develop into a structure around which you can weave a story.

“I try to be disciplined when I’m writing and to get at least something down every day, even if it’s rubbish.

“I write best early in the morning, so I get up before everyone else, make cup of strong coffee and lock myself away in my lair, surrounded by my special river things.

“I have nine-year-old twins (they were only four when I began writing Mudlarking), so starting early also means I can get a few hours in before school chaos starts.

“If I don’t have any other work, I go back to my writing desk once everyone is out of the house and usually carry on writing for as long as the words flow."

Global reaction

“The feedback from Mudlarking has been incredible, mostly from the UK, but people write to me from all over the world.

“They are fascinated by what can be found in the Thames, but Mudlarking also seems to have struck a deeper note.

“I get messages from people who have lived in London or grew up along the Thames and moved away from it.

“The book seems to have reconnected them with the river and in many cases reminded them of their childhoods, picking up interesting things with their parents along the foreshore.

“For many it also became a ‘lockdown book’, a way to escape COVID confinement."

Media star

“I’ve had a lot of media interest over the last two years.

“Mudlarking was BBC Radio Four’s Book of the Week and was reviewed in newspapers and magazines all over the world, including all the major UK newspapers.

“I’ve also done features for the Telegraph, New York Times, Financial Times, Reuters, the Washington Post, the Spectator and the Guardian.

“I’ve been on TV and radio with it too, including a short series for BBC Radio Three, the Smithsonian Channel, the Travel Channel, and Michael Buerk’s How the Victorians Built Britain.

“The Field Guide has only just come out, but it’s getting some great reviews and there’s more features coming throughout September."

Festival plans

“For the last five years or so I’ve done foreshore walks at Thames Tidefest.

“It’s a really lovely little river festival at Strand-on-the-Green. This year (12 September), I’m also signing books.

“It’s great for families and they always have loads going on, including river dipping for mini-beasts, kayaking, paddle boarding and history tours and walks.

“Greenwich is my part of London, so I’ll definitely be popping into the Totally Thames Rivers of the World exhibition at the National Maritime Museum too.”

Advice for would-be mudlarkers?

“First and foremost, make sure you get a PLA permit, and mudlark responsibly.

“The foreshore is a fragile environment, both historically and ecologically, so treat it with care and respect.

“I’d also ask people to only take what they need. There are a lot of bits of pottery and clay pipe stems down there, but just because they are there you don’t need to take them all.

“The objects you do keep need to be recorded, if they are archaeologically important and over 300 years with the Portable Antiquities Scheme (www.finds.org.uk), otherwise their provenance and story will be forgotten.

“It’s also important to share what you find, show other people, post them on social media, shout about them! They tell the story of us, it’s our shared history. It should be just that - shared.

“I should also mention that I don’t use a metal detector, or dig, or scrape the foreshore. I take a gentle, and non-invasive approach, everything I find is delivered by the river and left for me on the surface by the retreating tide.

“And, of course, for the practical side of things - where, when and how - buy my new book!”

Quick Fire

If you could time travel, what period of history would you go back to?

The reign of Elizabeth I. The river would have been such a vibrant and busy place, filled with wherries and ships, sumptuous river pageants to watch, theatres and riverside taverns to visit, fabulous riverside palaces and, of course, Old London Bridge for a bit of rapid shooting.

Person you’d most like to meet

King Cnut, who is believed to have built the first palace at Westminster, which was then called Thorny Island. I’d sit with him in his palace, look out over the wide-spreading, marshy-banked Thames and ask him if he really did try to hold its incoming tide back.

Favourite Thames walk?

St Katherine’s to Limehouse. You can do much of it on the foreshore at low tide and there are some good pubs along the way for rehydration. My mother’s family were ship builders on the Thames from the 1840s and they lived in Wapping and Limehouse, so there are family ghosts on this stretch.

More information:

- Instagram: @london.mudlark

- Facebook: @londonmudlark

- Twitter: @londonmudlark

Related content

Discover